photo: ®Uplift, Trickle UP program

This Insight originally appeared in Policy in Focus, Volume 14, Issue 2, July 2017, Brasilia: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth, and is published with permission.

The Data reported in this article are based on the information summarised in CGAP (2016).(1)

About the Authors: At the time of writing, Aude de Montesquiou(2) was Financial Sector Specialist for Policy and the Task Team Leader for the Graduation and Vulnerable Segments Initiative at CGAP. Syed M. Hashemi(2) was serving as a Consultant to CGAP concentrating on identifying pro-poor innovations and disseminating best practices related to poverty outreach and impact, including the development of social performance indicators for tracking changes in the social and economic levels of MFI clients.

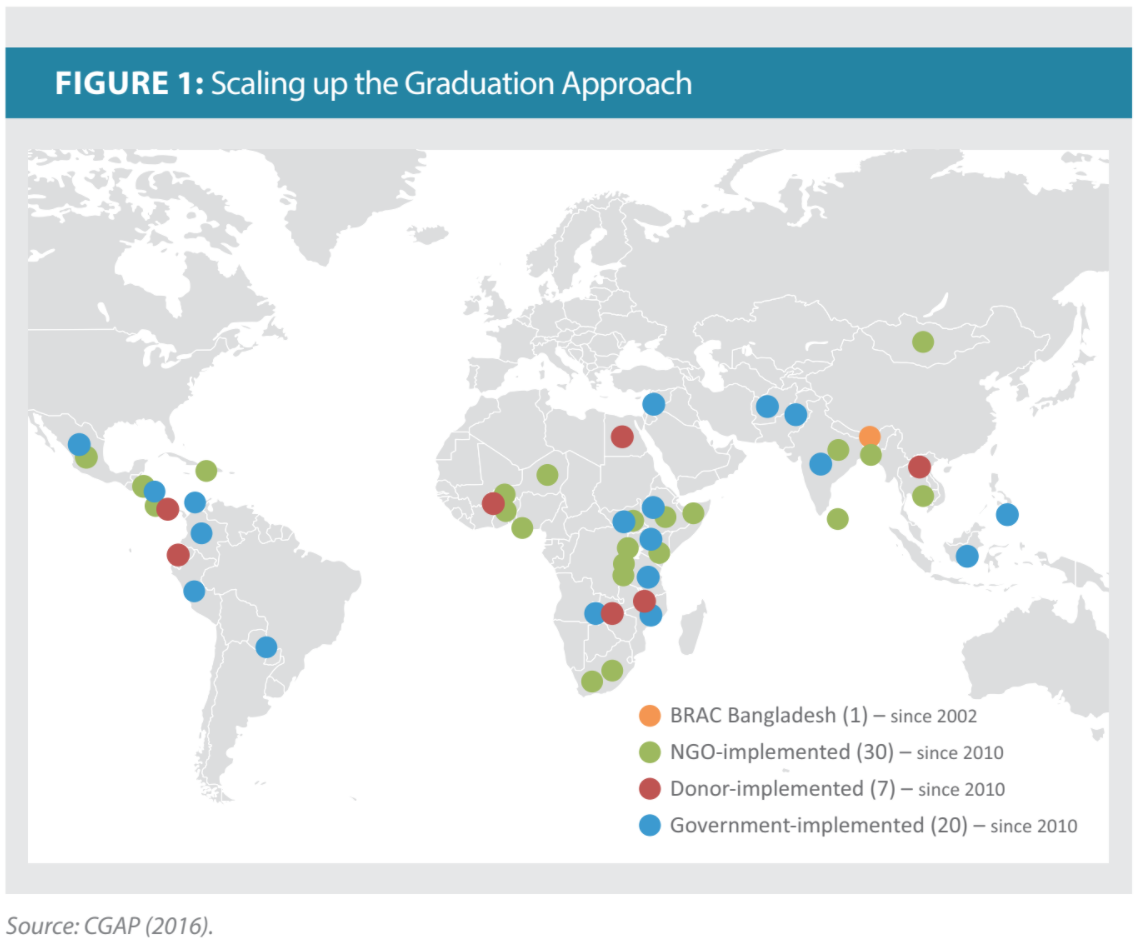

Governments, donors and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) attempting to reduce extreme poverty are increasingly implementing graduation-type interventions as part of their social protection strategies, to create sustainable livelihoods for many of the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people. The global commitment to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 1 “End poverty in all its forms everywhere” by 2030, the rigorous evidence-based proof of concept,(3) the adoption in varied regional contexts, the successful scale-up in many countries, the adaptation to different vulnerable groups, and the extensive coverage in academic literature and the popular press have all contributed to the heightened interest of policymakers and donors in graduation approaches. These are growing fast, with 57 graduation programmes now implemented in nearly 40 countries,(4) of which a third are being led by national governments. Figure 1 shows the time-lapsed proliferation of graduation programmes and the diversification of different implementers since 2002.

FIGURE 1: Scaling up the Graduation Approach

CGAP (2016) provides a rich set of information drawn from these programmes that allows us to make general observations on the global trends of graduation.(5) Over 2.5 million households have been reached to date through graduation programmes. The average size of a programme is approximately 42,475 households, and the median size is 1,350 households, indicating that programmes widely vary in size, ranging from a mere 150 households in Nicaragua to 675,000 households in Ethiopia. Programmes included in the CGAP inventory are projected to reach an additional 1.2 million households in the near future.

The Graduation Approach

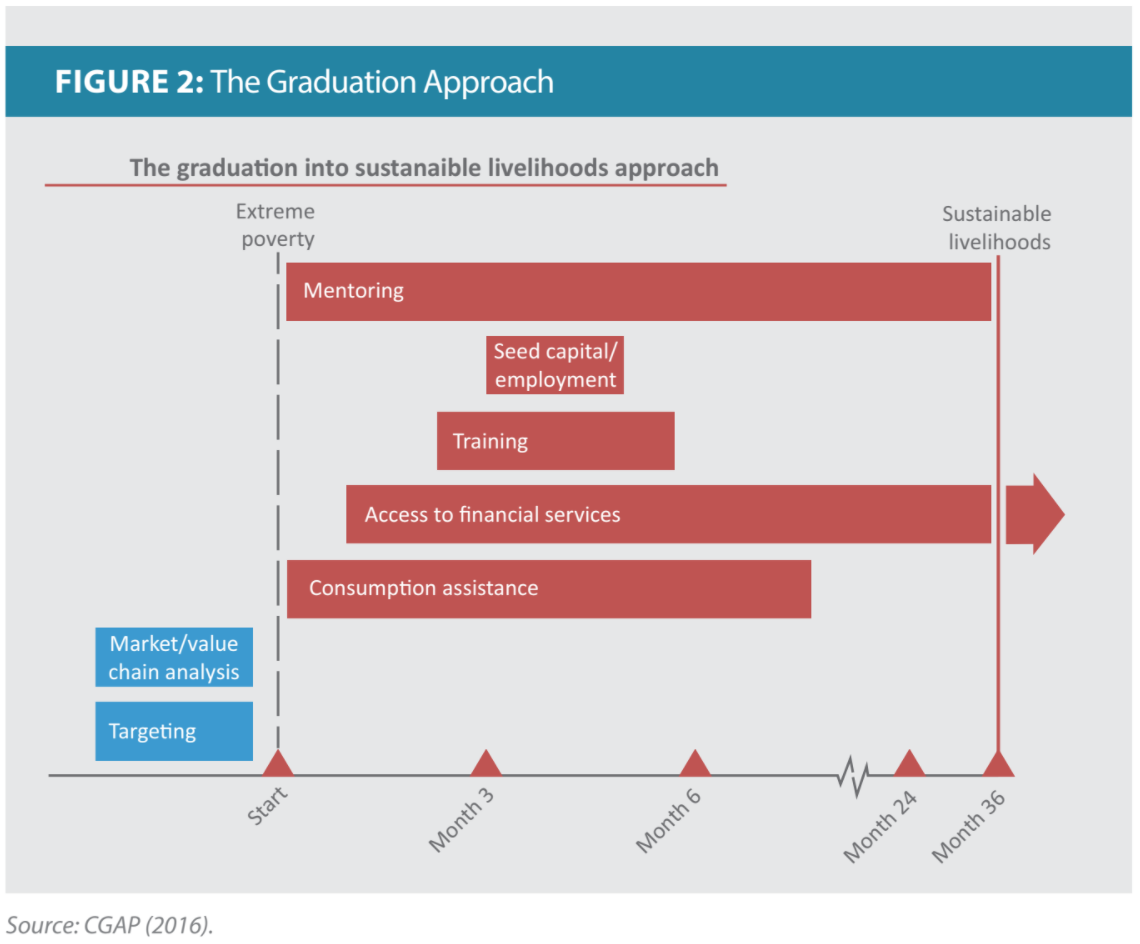

Graduation programmes have been adapted to specific objectives and contexts. However, they share some common characteristics (see Figure 2):

- They are time-bound (generally 24 to 36 months), household-level interventions deliberately targeting extremely poor people—either those living under the international poverty line of USD1 .90 per day and/or thoseidentified as the poorest, the most marginalised or the most vulnerable.

- They are a carefully sequenced, holistic effort, combining social assistance, livelihoods and financial services to tackle the multifaceted constraints of extreme poverty.

- They represent a ‘big push’ (seed capital and/or training for jobs based on the idea that a large investment to kick-start an economic activity is necessary to make a meaningful change.

- They are interventions that include some form of mentoring and staff accompaniment to help participants overcome not only their economic constraints but also the many social barriers they face, to essentially take control of their future. Additionally, many of these programmes facilitate access to other social protection initiatives and to financial services to build resilience and improved economic conditions beyond the duration of the programmes.

Reviewing the expansion of graduation

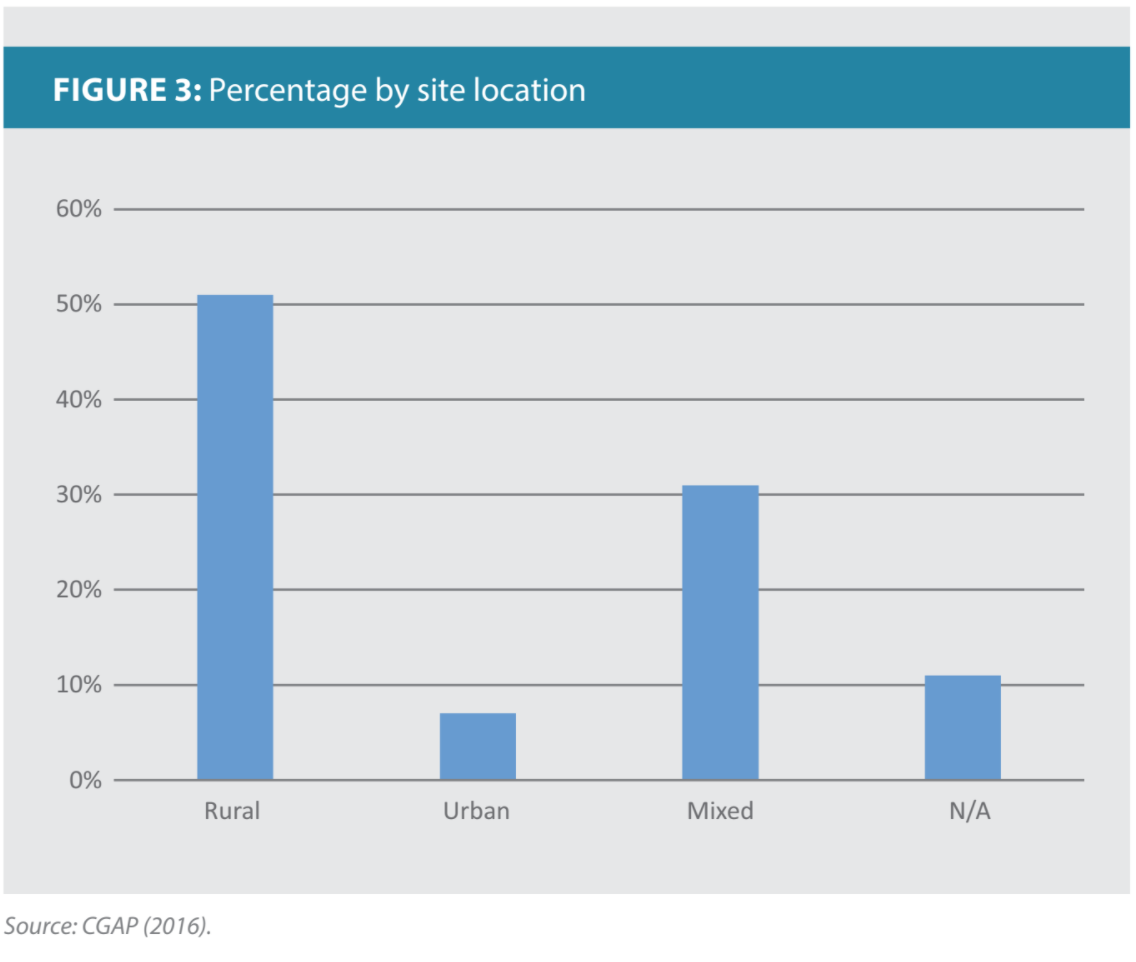

Over the past 18 months, graduation programmes have shifted their focus from predominantly targeting rural households (73 per cent in 2015 to 53 per cent in 2016) to mixed programmes, operating in both rural and urban areas (7 per cent to 31 per cent), and purely urban areas (2 per cent to 7 per cent).(6) This represents a fourfold increase in mixed and purely urban programmes since 2015 (see Figure 3) and reflects an increased concern with urban poverty. In fact, the extension of graduation approaches to urban areas has led programmes to recognise that linkages to employment opportunities (rather than seed capital for micro enterprises) would be a far better option, especially for the youth, to combat extreme poverty.

FIGURE 3: Percentage by site location

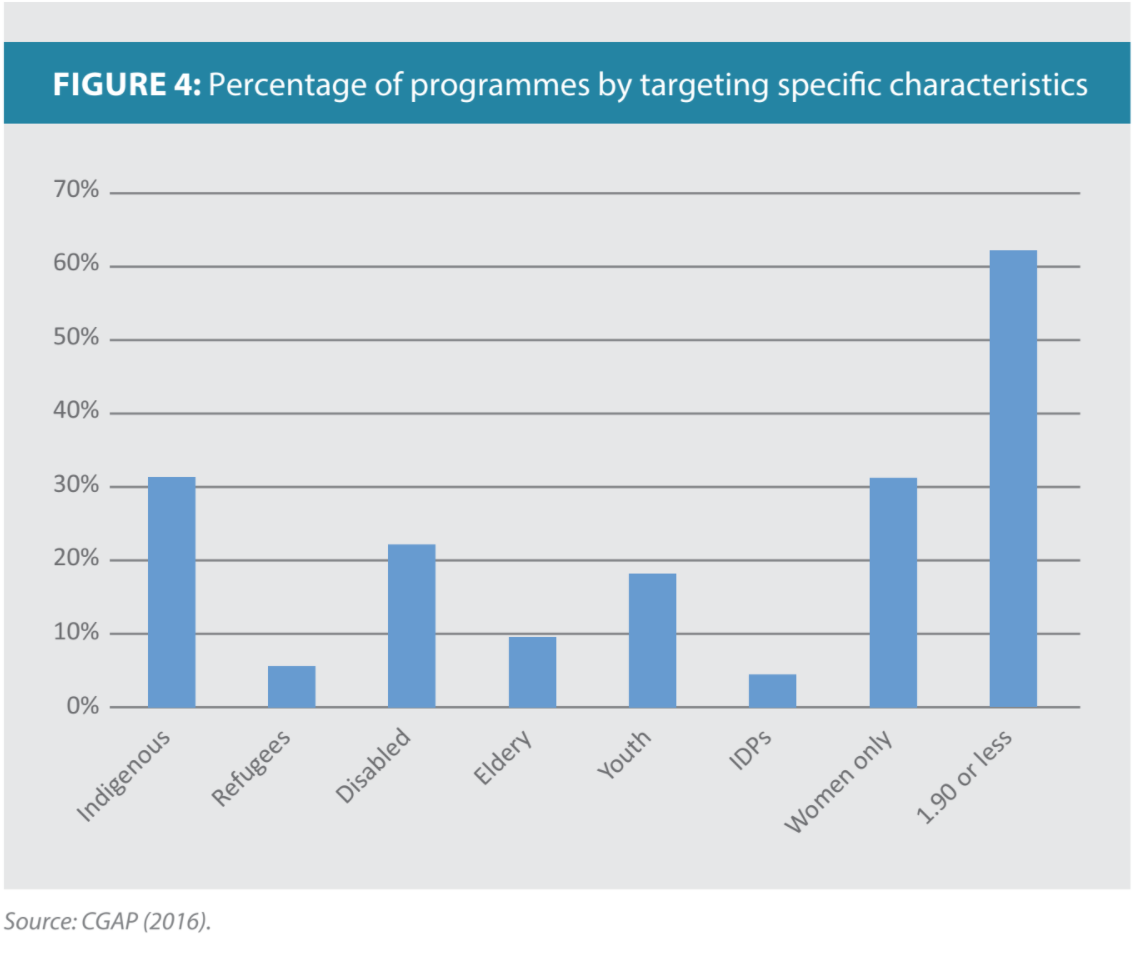

Targeting has also shifted from a predominant focus on women and the poorest people to a broader range of beneficiaries. Approximately a third of projects solely targeted women in 2016, and 60 per cent targeted populations living on less than USD1.90 a day, down from 73 per cent of programmes in 2015 (targeting populations living on under USD1.25 a day-the extreme poverty line at that time). There is a growing effort to adapt the Graduation Approach to other vulnerable and marginalised segments of the population, such as indigenous groups (31 per cent), refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs-9 per cent), youth (18 per cent), people with disabilities (22 per cent) and elderly people (9 per cent) (see Figure 4).(7)

Graduation programmes cost on average USD550 per household. This includes all costs (e.g. staff costs, programme overhead costs, transfers to participants etc.) for the entire duration of the programme.

While the sticker price of graduation programmes tends to be high, it is important to recognise that the potential benefits are also high. Randomised control trials (RCTs) conducted by the London School of Economics about BRAC schemes found that the total programme costs of USD365 would yield total benefits of USD1,168 over a projected span of 20 years (the discounted sum of consumption and asset gains in 2007 US. dollars). This would amount to a benefit-cost ratio of 3.2-or USD3.20 in benefits for every USD1 spent on the BRAC programme (Bandiera et al. 2016). Recent research also shows that among programmes targeting extremely poor people (livelihood development, lump sum cash transfers or graduation) and for which there is long-term evidence available, the Graduation Approach has the greatest impact per dollar, with a positive impact on economic indicators that persists over time (Sulaiman et al. 2016).

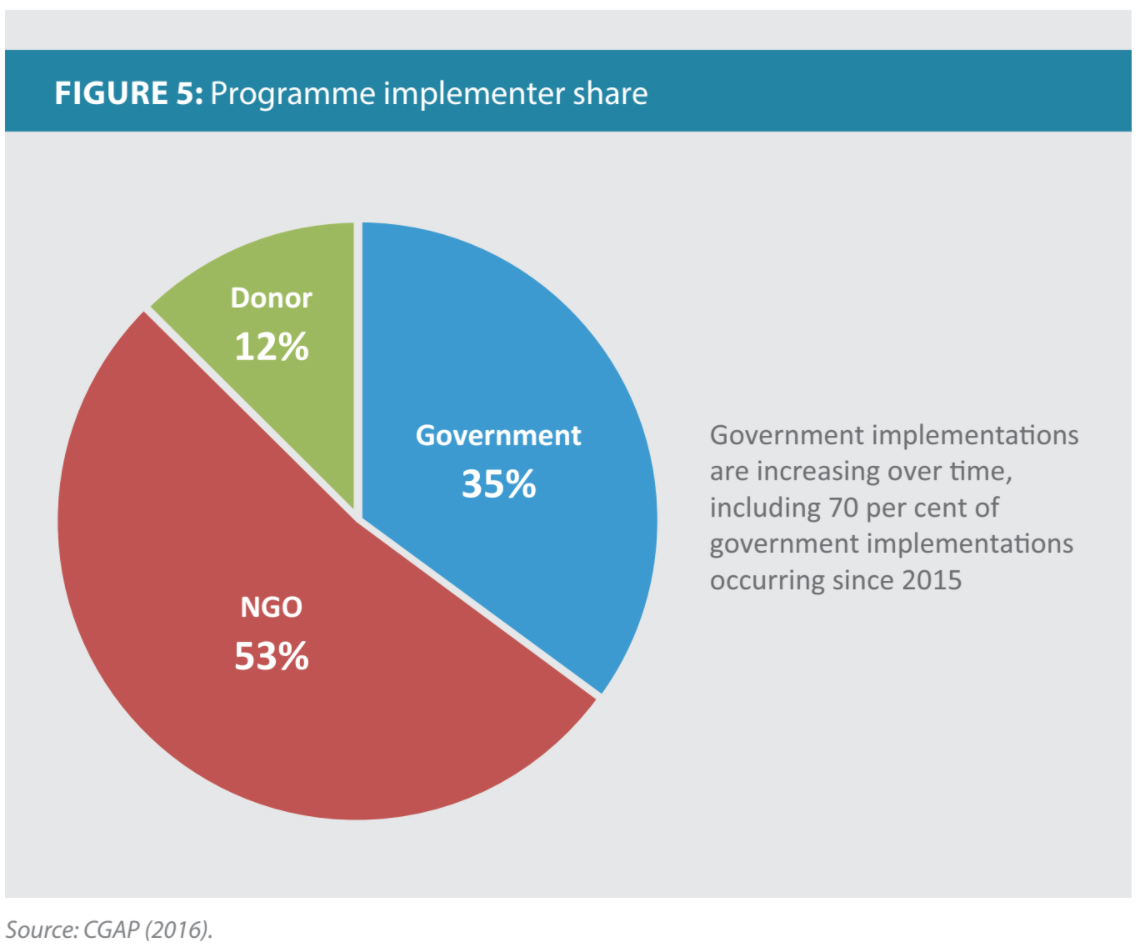

Figure 5 shows that a third of ongoing graduation projects are being implemented by governments, reflecting the growing interest in this carefully sequenced, multipronged approach as part of their national social protection initiatives. However, implementing such a holistic approach is particularly challenging for governments, who are the least likely to offer the‘full graduation package’to their beneficiaries (compared to NGOs or donors). In fact, 36 per cent of all graduation programmes do not offer the complete suite of interventions. While staff costs are part of the reason, limited governmental capacity in staffing front-line workers with the people skills necessary to work closely with beneficiaries is an important prohibitive reason. Governments, therefore, often exclude case management, technical training and the more labour-intensive activities from the graduation package.(8) Some governments are exploring ways to make the staff accompaniment or mentoring component of programmes easier to deliver.

In Ethiopia, for example, the government is layering the mentoring component onto its pre-existing social worker infrastructure. The Government of Colombia is exploring the use of technology with videotaped mentoring sessions delivered via tablets or social informational text messages sent to participants’ mobile phones. The Peruvian government’s Haku Wirtay programme is not implementing the staff accompaniment component at all, since it does not have the capacity to do so effectively. Rather, it is promoting the use of community volunteers as a resource for technical assistance, instead of paid programme staff.

In a number of countries, government commitment to scaling up graduation coincides with national initiatives to increase the availability and use of digital and non-digital financial services. Digital transfers hold strong potential to make delivery more convenient for recipients, while reducing the costs for project implementers. Eighteen per cent of projects have digitised part of the transfers, but more research is required on digitising components of graduation programmes and determining which components result in the greatest cost savings.

Challenges of scaling up

The key to successful implementation of the Graduation Approach is contingent on the following:

- Careful design to consider existing and potential livelihood opportunities, markets and prevailing cultural norms.

- Participatory and transparent targeting(9) to avoid confusion and conflict as well as to ensure that the appropriate beneficiaries are identified and included.

- Clear messaging around time-bound assistance to help catalyse and accelerate the planning for economic livelihoods. While safety net guarantees for those facing crisis and slipping back is integral to the social protection commitment we advocate for all, the Graduation Approach is designed as a time-bound ‘big push’for participants to quickly launch their livelihood activities and stay on course towards sustainability.

- Appropriate linkages to other social protection interventions as well as health care, schooling and financial services, so that participants can continue to improve their social and economic conditions beyond the duration of the programme.

- Hiring staff to ensure close staff-participant interactions and build the agency of the poorest and marginalised people.

The proliferation and scale-up of the Graduation Approach is, more importantly, conditional on easing many of the meso-and macro-level constraints. Market size represents an important bottleneck. Too many people pursuing the same micro-businesses or with the same employable skills will soon reach the absorptive capacity of the local economy and be out of work.

Unless there are concomitant efforts to expand markets through value chain analysis, market studies or local economic investments, the Graduation Approach will be ineffective for large numbers of the poorest people. Natural resources, the local ecology, climate variability and physical terrain all represent other major constraints. Arid or semi-arid zones, mountainous or sparsely populated regions, droughts or flooding can create conditions for low economic dynamism and low livelihood opportunities. The absence of basic social services such as health care facilities and schools increases morbidity and mortality rates and restricts the possibilities of preventing the intergenerational transmission of poverty. A low level of participation in local government reduces the chances of local budgetary expenditures for poor people. In addition, macro-level variables, such as economic mismanagement, corrupt governance, violence and conflict, as well as the vagaries of the global economy contribute to the creation of fragile States and severely constrain possibilities for reducing extreme poverty.

It is important to note that ‘graduation’ is only one pathway-a rigorously tested model-to reduce extreme poverty. Others, such as wage employment, may often be more effective. And additionally, the long-term success of the Graduation Approach is contingent on a comprehensive social protection regime that offers a range of risk-mitigating measures to address the many vulnerabilities faced by poor people.

In fact, what we advocate for are national social protection policies with graduation as an integral component.

The learning agenda

There is still much to learn. The graduation ‘Community of Practice’ is actively trying to do so—for instance, 71 per cent of graduation programme implementations include a research component to study their impact on beneficiaries.(10) Thirty interventions include RCTs as part of their research agendas.

Research focuses on a variety of topics: 42 per cent of research projects(11) will assess programme components, including adaptations and method of delivery, 27 per cent of projects will assess long-term impacts of graduation, and 11 per cent will conduct cost-benefit studies to provide policymakers with robust evidence to determine the effectiveness of graduation relative to other programmes. There is keen interest in innovations and knowledge—sharing to:

1) Adapt the Graduation Approach to additional vulnerable segments of the population, including refugees, extremely poor urban households and disadvantaged youth or children. 2) Expand the range of income-earning options beyond rural livelihoods to safe and decent employment. 3) Provide better linkages to meso-level interventions, such as schooling, health care, and climate change and disaster mitigation programmes. 4) Improve cost-effectiveness through measures such as digitisation of transfers and financial services, case management and advice through volunteer groups or existing social support, and leveraging existing government services. 5) Ensuring closer convergence of formal government social protection and other programmes for vulnerable people.

Looking ahead

The Graduation Approach is expected to continue to grow in scale and influence, with strong demand from donors and governments for nationally scaled programmes. CGAP is actively working with the World Bank’s Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice as well as members of the global Graduation Community of Practice to develop a dedicated, autonomous platform for graduation efforts, as part of the broader social protection agenda. The platform will serve and support governments and other stakeholders, bringing them together so that they can implement household-level, holistic, income-earning interventions for extremely poor households and other vulnerable populations by focusing on five key activities:

- Advocacy: Scaled adoption of effective graduation-style programmes for extremely poor people and better integration within social protection systems. Government implementations are increasing over time, including 70 per cent of government implementations occurring since 2015.

- Knowledge generation and innovation: A set of proven scaled models by context and levels of resourcing/social protection budgets; an established process for ongoing innovation; clarity on adaptations to additional vulnerable segments; and proven efficiencies through digitisation and other innovations.

- Knowledge management: A robust global database of intervention design and implementation guidance, technical tools, best practices, technical service providers and ongoing/completed research that is accessible and used for building graduation pathways.

- Compliance with standards: An established and widely accepted set of standards and methodologies for evaluating programmes and any new interventions.

- Sustainable Resourcing: A sufficient and diversified set of funders and funding tools to support countries and programmes to ensure that extremely poor and vulnerable populations have access to effective programmes and ongoing support needed for resilience.

The platform will serve the Community of Practice with critical public goods, test new solutions and magnify the impact of targeted investments in economic inclusion by governments, development agencies and others.

Sources:

Bandiera, O. R. Burgess, N. Das, S. Gulesci, I. Rasul, and M. Sulaiman. 2016.“Labor Markets and Poverty in Village Economies.” Quarter/y Journal of Economics.

Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, N. Goldberg, D. Karlan, R. Osei,W. Parienté, J. Shapiro, B.Thuysbaert, and - C. Udry. 2015. “A multifaceted program causes lasting progress for the very poor: Evidence from six countries.” Science 348(6236): 1260799.

CGAP. 2016.“State of Graduation Programs 2016.” CGAP Microfinance Gateway website. Accessed 24 April 2017.

Hashemi, S., A. de Montesquiou, and K. McKee.2016. “Graduation Pathways: Increasing Income and Resilience forthe Extreme Poor”. CGAP Brief. Washington, DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor. Accessed 3 May 2017.

Sulaiman, M., N. Goldberg, D. Karlan, and A. de Montesquiou. 2016.“Eliminating Extreme Poverty: Comparing the Cost-Effectiveness of Livelihood, Cash Transfer, and Graduation Approaches. Comparative analysis of three strands ofantiepoverty social protection interventions.” Washington, DC: Consultative Group to Assist the Poor and Innovations for Poverty Action. Accessed 24 April 2017.

Notes:

- The data reported in this article is based on the information summarised in CGAP (2016).

- The Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP).

- See Banerjee et al. (2015) and Bandiera et al. (2016).

- Although we have identified 57 graduation programmes globally, we received completed questionnaires from 55 programmes. The analysis in this article is based on these 55 programmes.

- Five of the 55 programmes were not included in the report due to limited information. See CGAP (2016).

- Eighteen per cent of programmes in 2015 and 11 percent of programmes in 2016 did not provide complete information on regional distribution.

- Seventeen per cent of the sample did not report information on targeting; some reported targeting more than one group.

- Total supervision costs (salaries of implementing organisation staff, training materials, training, travel costs and other supervision expenses) amount to 44 per cent of total programme costs, on average, in Ethiopia, Ghana, Honduras, India and Peru (Banerjee et al.2015).

- Some in the development community have critiqued ’targeting’ as ineffective, exclusionary and expensive, opting to support universal coverage. However, we feel strongly that while targeting is not 100 percent accurate in avoiding all inclusionary and exclusionary errors, it is the most effective methodology for including specific segments of the poorest population in graduation approaches in a cost-effective, open, participatory manner and in a budget-constrained environment.

- Only 2 per cent of the sample did not report research practices.

- Calculations are based on 36 projects that provided specific impact assessments questions. See CGAP (2016).